Hunger makes creativity show up fast, especially when the pantry looks painfully bare. These wartime meals might sound unappetizing today, but they kept families going when rations were thin and options were thinner. You will see how scraps, cans, and humble vegetables turned into survival food with surprising heart. Peek into the pots of the past, and you might even find a few thrifty tricks worth saving.

Ration food

Ration food meant learning a new rhythm at the stove. Small portions had to stretch across long weeks, and every crumb mattered. You weighed sugar, cut butter thin, and made tea leaves work twice. It was not glamorous, but it was careful.

To make it edible, cooks leaned on seasoning, thrift, and patience. You might boil bones for broth, swap meat for beans, and mash root vegetables into filling sides. The goal was satisfaction more than taste. You learned timing, planning, and how to transform scraps into something warm enough to keep hope steady.

Potato meal

Potatoes were the dependable friends of hard times. You could boil them, mash them, fry leftover mash into cakes, or stretch them into stews. Even peels were saved to crisp in a pan with a whisper of fat. Salt and vinegar were prized allies.

Sometimes you mixed mashed potato with flour to make rough dumplings. Other days, you sliced them thin and baked until edges went golden. You did not need much to feel full. Potatoes carried weight, warmth, and a kind of comfort that lingered long after the plate was cleared.

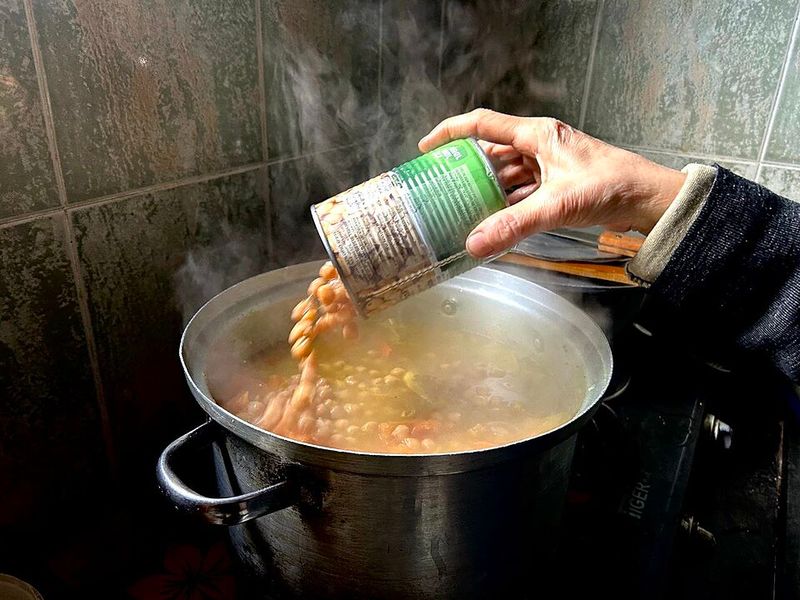

Canned food

Canned food was both lifeline and compromise. The texture could be soft or rubbery, and flavors leaned salty. But those tins sat steady on shelves when markets emptied. You learned to coax them into meals you could recognize.

Spam fried crisp gave sandwiches backbone. Evaporated milk turned into sauces or desserts that felt almost fancy. Tinned peas and carrots brightened stews, even if the color lied a little. With a can opener and a hot pan, you could build dinner fast. It was dependable, predictable, and sometimes, with a good sear, even satisfying.

Simple porridge

Simple porridge made mornings carryable. Oats simmered with water or watered milk until thick and gentle. You stirred steadily, adding a pinch of salt to wake the grain. Sweetness, if any, came from a spoon of treacle or a sprinkle of sugar saved from coupons.

Leftovers never wasted. Cold porridge could be sliced and fried into golden slabs. The crust crackled and the inside turned tender again. It felt honest. You ate with a big spoon, let the warmth soak in, and faced the day with something steady in your stomach.

Flour and water

Flour and water sounded bleak, but it built the base for everything. You mixed, kneaded briefly, and pinched in salt. Sometimes a spoon of fat made miracles. Flatbreads hit a hot pan and puffed in spots, then softened under a towel.

The same dough thickened stews or turned into dumplings. You learned to stretch flavor with onion, drippings, or a smear of jam when lucky. It felt like alchemy, turning almost nothing into something chewable. Not glamorous, not even pretty, but it kept hunger from biting too hard.

Vintage kitchen

The vintage kitchen told the story before a pot even warmed. Enamel bowls chipped from years of scraping. A coal stove glowed dull red, turning everything faintly smoky. Ration posters reminded you to save every crumb and grease jar.

Tools were few, but hands were clever. You used one sharp knife for everything and kept it honest with a worn steel. Measuring happened by eye, by feel, by memory. The air smelled of toast, cabbage, and soap. It was not romantic then. It was just where survival got sorted out daily.

Tin cans

Tin cans did more than feed people. After the contents left, cans became cups, scoops, planters, even lanterns punched with holes. You saved every bit of wire and string to make handles. Waste was a luxury no one could afford.

In the kitchen, cans cut biscuits and stored grease. Kids used them for toys, sliding pebbles inside for rattles. Labels peeled away, leaving plain metal that felt honest and hardworking. Each can told a story of thrift. Even the sharp edges taught caution and care in a world running thin.

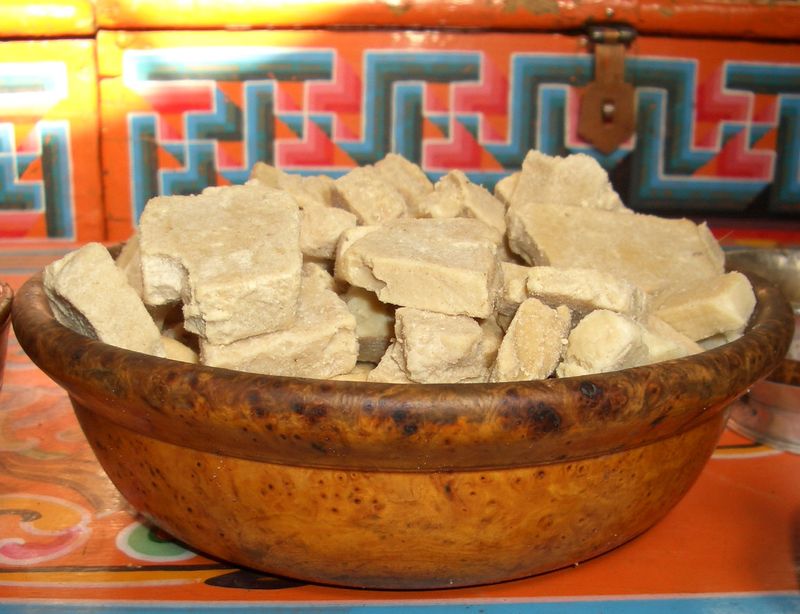

Basic ingredients

Basic ingredients kept spirits steady. Think onions, carrots, potatoes, dried beans, and salt. When those were around, you could build flavor from almost nothing. Fry onions low until sweet, add carrots for color, then let beans or potatoes carry the weight.

It taught patience. You cooked slow to draw everything out and avoided wasting a single peel. Even pepper felt like celebration. With time, water turned into broth, and thin ideas became meals. You learned taste comes from attention as much as from luxury.

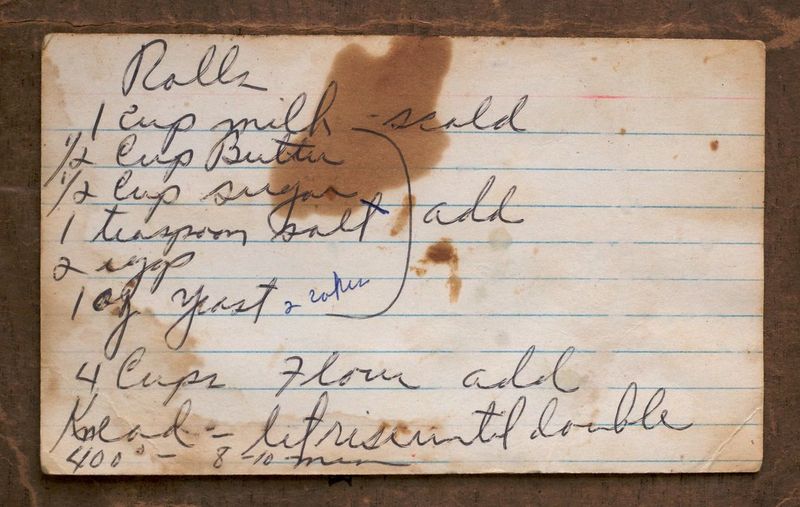

Old recipe card

An old recipe card felt like a voice across years. Stains marked the spots where hands paused and splashed. The handwriting curled with certainty, even when the ingredients were sparse. You trusted it because someone cooked it through hard days and lived to rewrite it.

Notes whispered substitutions: dripping for butter, barley for rice, treacle for sugar. You followed and felt guided. The card belonged to the family and the times, stubborn and practical. Cooking from it felt like keeping a promise to people who stretched every scrap.

Boiled vegetables

Boiled vegetables were a staple, even if the smell lingered through the house. Cabbage, carrots, and turnips softened into something filling. You salted the water and saved it for soup, because every bit mattered. Butter was rare, so a drizzle of dripping made it feel complete.

Leftovers turned into bubble and squeak with a quick pan fry. The edges crisped, and suddenly dinner tasted like something you craved. It was not fancy, but it was faithful. Vegetables carried families when meat coupons disappeared.

Bread slices

Bread slices meant comfort and structure. A loaf had to last, so cuts were careful and even. Stale bread became an asset, ready to toast, crumble, or soak into custards made with watered milk. You respected the heel for its sturdiness.

You might rub garlic on warm toast, spread dripping paper thin, and call it dinner. In soups, cubes turned into floating croutons. Every slice felt like a small decision about tomorrow. Bread centered the table and quieted worries for a while.

Thin soup

Thin soup carried dignity in a small bowl. The broth started with bones, peels, or saved cooking water. A few vegetables, sliced small, stretched across servings. You salted just enough to steady the flavor. It warmed hands first, then stomachs.

On hard days, stale bread thickened it. On better days, barley or oats joined to give it body. You learned to layer flavor with time rather than abundance. The steam felt like a little kindness. Even thin, it tasted like persistence.

Root vegetables

Root vegetables survived storage and kept cooking going through winter. They were earthy, steady, and honest. You scrubbed them, saved peels for stock, and cut away just enough to lose the dirt but not the dinner. Turnips and beets stood in for luxuries you did not have.

Roasted, they developed sweetness that felt like a reward. Mashed, they filled plates with humble color. You learned respect for anything that grew quietly underground and kept families upright when markets were bare.

Simple stew

Simple stew turned scraps into supper. You browned onions in a whisper of fat, added potatoes and carrots, then barley for heft. Meat scraps, if any, were precious. They flavored the pot more than they filled bowls. Long simmering made everything friendly.

Leftovers improved overnight, thickening as starches relaxed. You could stretch it with water and call it new. Fresh herbs were rare, so dried thyme stood in. It tasted like patience and planning, which felt like abundance under the circumstances.

War era cooking

War era cooking was not about show. It was survival with a side of stubborn optimism. You counted coupons, saved fat, and planned a week with two onions and a dream. The stove was hot, the knife was sharp, and waste was a sin.

Recipes flexed constantly. Substitutions were normal, criticism rare. Everyone understood the stakes. You learned to season with time, toast, and technique more than spice. Meals were modest, but they arrived on time. That reliability mattered as much as flavor.

Food rationing

Food rationing rewired habits. Suddenly, choices were not about cravings but calendars and coupons. You planned meals around what you could actually acquire. Butter and sugar became rare notes rather than chords. People swapped tips in queues and traded spare coupons with neighbors.

Rationing also inspired creativity. You used carrot in cakes, dried fruit for sweetness, and powdered eggs for baking. Waste carried guilt. Cooking turned strategic, even communal, because everyone was figuring it out together. It shaped taste for years after.

Empty pantry

An empty pantry could still yield dinner with enough nerve. You took stock, lined up the odds and ends, and asked water to do heavy lifting. Oats thickened soups. Half an onion made the house smell hopeful. A potato could anchor the whole plan.

You leaned on technique. Toast dry spices, brown scraps, and layer flavors. Thin meals need extra attention. You tasted more, stirred longer, and served hot. Heat and timing made scarcity feel a little kinder.

Old stove

The old stove defined the pace. Coal took coaxing, and heat zones were learned by hand. You kept a kettle always ready, because hot water solved many problems. Bread rose near the warm side, while soups simmered at the fringe.

It was temperamental but honest. You could not rush it, so you adapted. The stove taught patience and attention. In return, it gave steady heat and reliable meals. That felt like safety when everything else shifted.

Minimal meal

A minimal meal sometimes meant one good bite made well. A single potato cake, crisp at the edges, could feel like a win with a spoon of gravy. You focused on texture and temperature. Serve it hot and salt it right. That was the trick.

Small plates slowed you down. You noticed flavors more when there were fewer of them. Gratitude grew in the quiet. It was not enough, but it reminded you that skill could still make a difference.

Survival food

Survival food has one job: keep you going. Hardtack, dried beans, canned meat, and powdered milk may not win applause, but they show up when needed. You plan around shelf life, not cravings. Boil, soak, and soften until the hard things give in.

Seasoning is strategy. A bay leaf here, a fried onion there, and a squeeze of anything acidic. The goal is fuel that feels like a meal. It is endurance on a plate, and sometimes that is enough.

Historical meal

A historical meal reminds you that taste travels with time. On the plate, you might see boiled potatoes, a slice of spam, peas, and thin gravy. Dessert could be carrot pudding or a syrup sponge made with watered milk. It is humble, structured, and strangely grounding.

Eating it connects you to people who managed more with less. You taste thrift, patience, and ingenuity. It is not just about flavor. It is about remembering what grit looks like at dinnertime.

Bread and soup

Bread and soup kept bellies steady when variety disappeared. The soup leaned thin, often just a broth with onions, carrots, or cabbage floating like small treasures. Bread was sometimes stale, but that helped it soak up every drop. You could stretch one ladle into a meal.

Flavor came from patience and salt, sometimes a bone or herb stalk. You learned to toast the bread, rub it with garlic if lucky, and spoon soup on top. The ritual mattered. Every bowl felt like a quiet promise that tomorrow would still be manageable.